Predestination in the Eastern Fathers

Theological Letters

A quick note: I’m producing The East-West Series, a comprehensive 25-lecture exploration of the theological differences between Eastern and Western Christianity. We’re crowdfunding to complete production — watch the trailer and learn more at theeastwestseries.com.

Fervent followers may be aware that I have an unfinished series on predestination published here on Substack. While I assure you, the final installment will indeed be published, here is a teaser to tide you over. You don’t need to read parts 1 through 3 to enjoy this piece, but in case you’re interested, here they are.

Dear “Eli,”

Thank you for your kind remarks about my work. I do plan to post part 4, but it is stuck in the queue behind other things.

By way of preview, I’ll say this about the Eastern fathers. I’ll begin by saying you find several things that are not particularly surprising. First, you find them using “predetermination” or “predestination” or “foreordination” in reference to God’s selection of a person for a task, such as a prophetic role or David for kingship, or for his selection of a people, like Israel. Here, the term simply indicates God foreordaining according to his foreknowledge a delegate for a role or task he wishes someone to do.

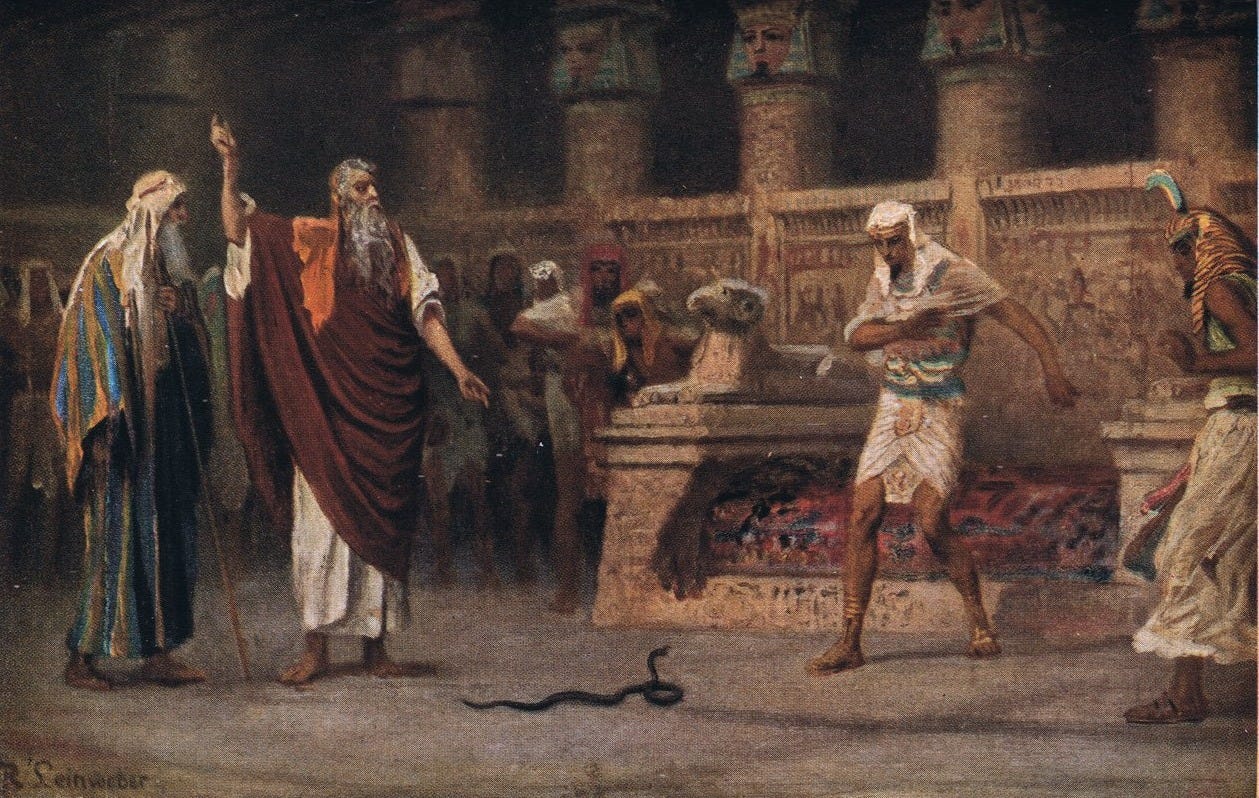

Second, you find remarks similar to what you find in the pre-Augustine Latin writers, namely, that election is based on a dynamic interplay between the creature’s responsiveness to God and God’s active work of redemption toward all creatures. To wit, salvation is synergistic in nature, resulting from the gracious work of God toward the creature and the creature’s cooperation. If you look in my earlier letter on predestination or my letter on free will, I mention that the Eastern fathers often use agricultural metaphors, in echo of Christ. For example, the sun shines on all soil without bias, and good soil flourishes while bad soil withers and cracks. They see something similar in the salvific interplay between God and creatures. God has a singular movement toward his creatures. God wills their good and his dealings with man are universally aimed at our salvation, but the effect that his operations have on us varies depending on our condition. God treats Pharaoh and Moses identically -- presenting himself to them, declaring himself to be God, demonstrating it by miracle, and making a demand. Moses, being good soil, flourishes into a Saint. Pharaoh, being proud and thinking himself a god, hardens and cracks. The difference is found in the recipient, not in the disposition of God. God being Good wills the good, and thus the salvation, of all, taking no pleasure in the death of the wicked.

Of course, there is the difference that the Latin writers think in judicial terms, speaking of the merits of one before God and the demerits of another before God, and thus think of grace in terms of mercy and aid in doing good. The Eastern fathers, by contrast, understand grace to be divine energy, the processions of the divine nature that we imbibe through Christ and the Holy Spirit through repentance and cooperation with God, the result of which is theosis, or deification. Hence, in the Latin West, grace is an effect upon the creature, whereas in the East, grace is God’s own energies at work in the creature. This is why the Latin West speaks of created grace while the East speaks of uncreated grace. (I trust I don’t need to explain the essence-energies distinction or theosis if you’re a regular reader of Theological Letters, since these topics come up often. But if you’re unfamiliar, let me know, and I’ll point you in the right direction.)

The more novel and fascinating feature of the Eastern patristic view of predestination concerns the doctrine of the logoi. By way of context, the Eastern fathers (and the Latin fathers) were realists. That is, they believe the “universals” that the mind identifies by genus, species, and common properties are real outside of the mind; they are not mental fictions. Like the Platonists and the Alexandrian Jews before them, they believe that God has archetypal Ideas of these structures, which our minds, as images of God, recognize. Hence, we know what a circle is by reference to the divine Idea of a circle, and we judge this particular circle good because it closely approximates that archetype and that circle as bad because it diverges from that same archetype.

However, the Eastern fathers take an additional step in their brand of realism that the pagans do not, and the Eastern fathers do so because of the doctrines of Trinity and Christology. To wit, they explore the concept of the particular subject or “person” (though I don’t care for this as a translation of hypostasis, but for more on this, see my various writings on the Trinity). In other words, the pagans focused largely on the phenomenon of universals but had given little thought to the enduring subject who has or participates in those universals. Yet, the Christians, recognizing that the Trinity is beyond both matter and form and yet consists of three subjects, and also recognizing that there is only one subject who has the natures of God and of man in the Incarnation, were forced to grapple with the question: What is the enduring subject? From this question emerged the doctrine of the hypostasis. That is, every nature is a mere abstraction and has no stability, or stasis, unless made concrete and stable within a subject, or hypostasis. (For a full treatment, see my article on the metaphysical idealism of the Eastern fathers.)

The importance of this insight is that the subject is not an illusion or a phenomenological byproduct. It is not a transient accident of matter or an artificial fantasm produced by an idiosyncratic cluster of properties. Rather, the subject is its own enduring reality, a substance beneath the universals and who gives stability, reality, and concrete existence to those universals. (Again, see my article on their metaphysical idealism.)

The importance of the point emerges when considering the doctrine of creation out of nothing. Unlike the pagans, the Christians insist that all that exists is created by God. Because the subject is its own substantial reality, that means that each particular subject, too, is created by God. And here we arrive at the doctrine of the logoi.

While the Eastern fathers do refer to divine ideas or concepts or thoughts about the things God intends to make, thereby echoing the Platonists and Alexandrian Jews, they also speak about the “words” (logoi) of God, harkening to the Genesis account. (This, too, I discuss in that piece on the metaphysical idealism of the Eastern fathers.) These logoi exist within the Logos, the second person of the Trinity, as God’s designs for the world laid bare in his Wisdom before the world existed. (Though the language here may be novel, the concept is not. The Platonists are known for talking about the archetypal Ideas within the divine Nous, or mind, and in Alexandrian Judaism, Philo of Alexandria talks about God having archetypal Ideas about his designs for the cosmos, which are within the divine Logos, a sentiment echoed by Origen as well as by Augustine in the Latin West. But amongst the Eastern fathers, the term logoi is used in place of ideas to wed the concept more closely to Genesis, where God has a concept of what to make and then speaks it into being, scattering those words into matter.) Now, unlike in the pagan conceptions of creation, where the divine Ideas include only generics -- generic man, generic dog, generic plants -- the Eastern fathers conclude that God’s Ideas or words, logoi, must include the particular subjects he intends to make -- not just man, but Adam, Eve, Cain, Abel, Seth, etc. Hence, while God has a design of man in the generic (a rational animal who is bipedal, etc.), God speaks into being particular subjects who have human nature.

The importance of this doctrine is that God’s designs include an archetype of what each one of us is made to become, our idyllic self -- you and I as Saints. This divine design, your logos, resides in the Logos, along with all of God’s designs for the cosmos. This, say the Eastern fathers, is your predestined end. In Christ, you are predestined to become that.

Here, however, is a further twist. This predestined end is not causally efficacious. In other words, though you are predestined to that end, that predestination does not guarantee you reach that end. Rather, this predetermined archetype serves as the measure of whether your self-determination is good and in keeping with your logos, as foreordained by God, or whether your self-determination is corrupt, moving contrary to your predetermined end -- very much like the way a circle is judged good or bad by its archetype in the divine mind. Such self-determination is what Maximos the Confessor refers to as your tropos, or mode of being. Our tropos, or movement toward or away from God, determines whether we are shaping ourselves in accord with well-being or retreat into self-corruption.

Such an understanding informs a number of interpretive moves by the Eastern fathers. When Christ tells the wicked to depart because he never knew them, the Eastern fathers understand that to say, I do not recognize you. Whatever you have made yourself into, it is not the creature I set out to make. Such is also the importance of Paul’s word order, namely, that those God foreknew he also predestined to be conformed to the image of Christ; the inverse is not true, namely, that those he predestined to be conformed to the image of Christ he foreknew. For all are predestined to this end, but not all are foreknown, as indicated by the parable of the sheep and the goats where the wicked, as wicked, are not known by him. Such is also important to Ephesians, where Paul’s hearers are predestined in Christ and through Christ. In the causal reading, where predestination merely means a causal decree to become something, you can strike all statements about in and through Christ and the sentences mean the same thing, but Paul reiterates this over and over.

Such an outlook is also why the Eastern fathers focus so heavily on two further statements of Paul. First, God is not a respecter of persons. They plainly think that arbitrary salvation and damnation would be unjust and incompatible with the divine nature (see Origen’s On Prayer and other comments in the Philokalia of Origen, edited by Basil of Caesarea and Gregory of Nazianzus). But they also see it as incompatible with Paul’s claim that God is not a respecter of persons -- that is, he does not show favoritism, a fact that is an extension of his justice. Rather, God favors the righteous because they are righteous and disfavors the wicked because they are wicked. (See, for example, Cyril of Alexandria’s comments on John, the Apostle whom Christ loved, being favored because of his unique virtue precisely because Christ cannot favor arbitrarily.) Second, they also see in Paul’s words to Timothy the exhortation to cleanse yourself and make yourself a vessel worthy of God, indicating that whether we are vessels of wrath or mercy is determined by our worth, which is in our power -- again, think of the soil metaphor.

Well, you nearly have the whole of part 4 here! Be watching for the more expansive version on my Substack. I hope that helps.

Sincerely,

Dr. Jacobs

Don’t forget to pre-order the East-West series at the lowest possible price. I sincerely appreciate the support in this effort.

Somewhat tangential to this post, but David Bentley Hart has had pretty caustic things to say about the essence/energies distinction. (See, e.g., here: https://davidbentleyhart.substack.com/p/q-and-a-14; search for "Palamism.) I would be interested in your thoughts on his criticisms. Thanks!